What is Pay Per Mile?

If you’ve heard murmurs about a new “pay per mile” charge for drivers, you’re not alone. As more of us shift to electric and ultra-efficient cars, governments everywhere are grappling with a simple problem: fuel duty is fading fast, but roads still need paying for. That’s where pay per mile also called road user charging (RUC) or distance-based charging comes in.

Below, I’ll demystify what pay per mile is, why it’s being considered, where it already exists, how it typically works in practice, and what (if anything) is actually planned for the UK including the latest signals from Westminster.

What exactly is “pay per mile”?

Pay per mile is a way of funding roads where drivers pay according to how much they use them the distance they travel, rather than (or in addition to) taxes baked into fuel or flat annual fees. In its simplest form, you take an odometer reading and pay a set pence-per-mile (or cents-per-mile/kilometre) rate. In more sophisticated versions, the rate can vary by vehicle type/weight, emissions class, time of day, and location to reflect congestion and wear-and-tear.

Why shift from the status quo? Traditional UK motoring taxation leans heavily on fuel duty (tax on petrol and diesel) plus Vehicle Excise Duty (VED). As EVs proliferate, fuel duty revenues shrink, creating a growing fiscal gap unless a replacement is found. The Office for Budget Responsibility and independent analysts have been warning about this trend for years; continuing freezes in fuel duty also deepen the shortfall.

A pay-per-mile system flips the logic: you’re charged for use, not fuel burned

Why is pay per mile on the table now?

1) The revenue hole from EV adoption. EVs don’t buy petrol or diesel, so they don’t pay fuel duty. Many governments are now exploring (or introducing) distance-based charges specifically to ensure EVs contribute fairly to road upkeep. The UK’s fiscal watchdog has highlighted the long-term revenue risk from frozen fuel duty and electrification.

2) Fairness and efficiency. Distance-based charging can be designed so light, low-impact vehicles and off-peak travel cost less, while heavy vehicles or peak-hour urban trips cost more—aligning what you pay with the costs you impose (wear, congestion, pollution). That’s the logic behind modern RUC schemes internationally.

3) Smarter congestion management. Some cities use dynamic road pricing to manage peak-time traffic (e.g., Singapore’s Electronic Road Pricing), and are now upgrading from gantries to satellite-based systems (ERP 2.0) that could, in time, support more granular pricing.

Where is pay per mile already in place?

Plenty of real-world examples exist: some nationwide, some state- or city-level, and some focused on heavy goods vehicles (HGVs).

New Zealand (nationwide, light vehicles). Since 2024, NZ has extended Road User Charges (RUC)—long applied to diesel vehicles, electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids. EVs pay NZ $76 per 1,000 km; PHEVs pay less because they already pay some fuel excise when using petrol. You buy distance “licences” in advance and renew as you drive.

Iceland (nationwide, light vehicles). In 2024, Iceland introduced a distance-based charge for clean-energy vehicles. Passenger cars pay about 6–6.7 ISK per km, with lower rates for plug-in hybrids; the policy is designed to transition away from fuel tax while keeping EV momentum.

United States (state programs).

Oregon is a voluntary per-mile program for passenger vehicles. Participants pay about 2 cents per mile (rising to 2.3¢/mile in 2026) and receive credits for any fuel tax paid at the pump, so you don’t pay twice.

Utah operates a similar voluntary scheme where drivers can opt to pay ~1.11 cents per mile instead of a flat EV registration fee, with annual costs capped so you’ll never pay more than the fixed alternative.

Belgium (nationwide, heavy vehicles). Since 2016, Belgium has run a GNSS-based per-km toll for HGVs (Viapass), with rates varying by region, weight, and emissions class. It consistently raises substantial revenue and has pushed the fleet toward cleaner Euro standards.

Singapore (city congestion, moving to GNSS). Singapore’s ERP has long charged vehicles when passing under gantries in priced zones. It’s now rolling out ERP 2.0, a satellite-based on-board unit for all vehicles. For now, pricing principles are unchanged, but the tech foundation supports more flexible, distance-sensitive charging in the future.

The common thread: practical, working systems exist—from odometer-based New Zealand to telematics-enabled Oregon/Utah and GNSS truck tolling in Belgium.

How does pay per mile actually work?

Looking at what’s worked abroad and what UK reports have suggested, a pragmatic UK design would likely include:

A low, simple entry rate (e.g., fractions of a penny per mile), possibly applied first to EVs to restore parity while maintaining incentives to switch. Think-tanks have floated odometer-based approaches with readings at MOT to minimise new hardware and privacy controversy in the early years.

Fuel-duty credits or offsets for petrol/diesel users (à la Oregon), so people aren’t double-charged, with an eventual shift as ICE vehicles decline.

Caps so early adopters never pay more than an equivalent flat VED or registration fee, protecting low-mileage drivers and building acceptance (Utah’s model).

Tiered rates by vehicle weight and, over time, the option to introduce time- or place-based signals on the busiest corridors—borrowing from Belgium’s and Singapore’s tech playbooks if and when public confidence in the system matures.

Crucially, the UK would need to legislate privacy and data-minimisation up front, offering non-location options (simple odometer reporting) alongside any telematics choice. International experience shows transparency here is vital to public trust.

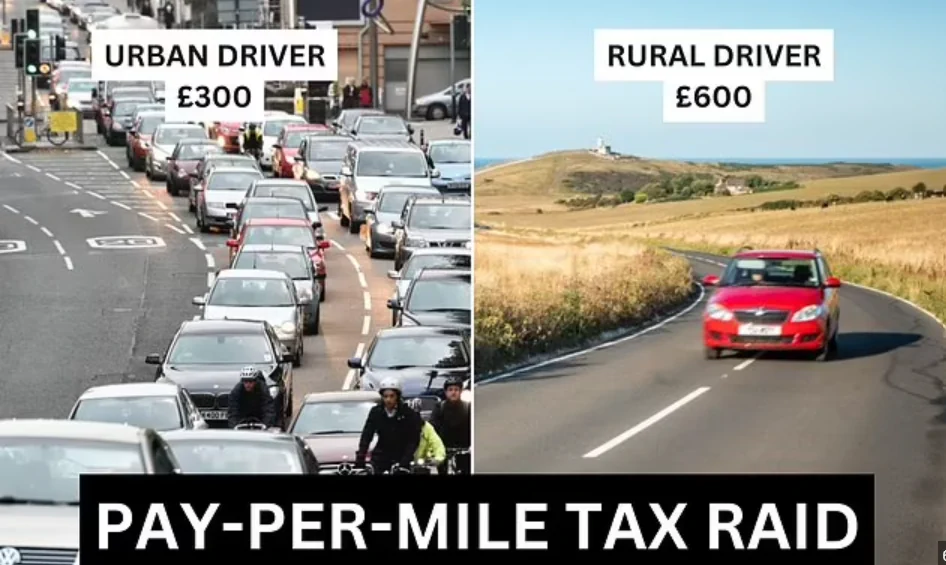

What would it mean for drivers?

Low-mileage drivers (many retirees, city dwellers) can be better off under pay per mile than under flat fees—especially if caps and credits are in place.

High-mileage or heavy-vehicle users would pay more in proportion to usage and impact a core fairness principle of RUC.

EV owners would start to contribute toward road funding, but smart design (low initial rates, caps) can avoid undermining the transition to zero-emission vehicles.

Where dynamic pricing is used (not all systems do this), off-peak and less congested routes can cost less, spreading demand and cutting jams.

Bottom line: necessary, yes; inevitable, maybe; imminent, no.

Necessary? From a public-finance standpoint, it’s hard to see a sustainable alternative to some form of distance-based charging as fuel duty fades. Even Parliament’s Transport Committee called it unavoidable.

Inevitable? Politically, road pricing is sensitive. Many governments (including the UK) are cautious. But the international trend, New Zealand, Iceland, Oregon, Utah, Belgium. This shows it can be done in ways that are practical, fair, and privacy-aware

Imminent in the UK? No official timetable. The government repeatedly states no plans for national road pricing as of late 2025. EVs have joined VED from April 2025, and fuel duty policy is slated to tighten in April 2026, but a UK-wide pay-per-mile start date has not been set.

If/when the UK does move, expect consultations, pilots, and a phased roll-out, likely starting modestly (EVs first, odometer readings at MOT, fuel-duty credits for ICE) before any deeper shift to time- or location-varying tariffs. That’s the pattern from places that have made it work.

Leave a Reply